Sarah Orne Jewett House

Sarah Orne Jewett House

Breaking the Mold

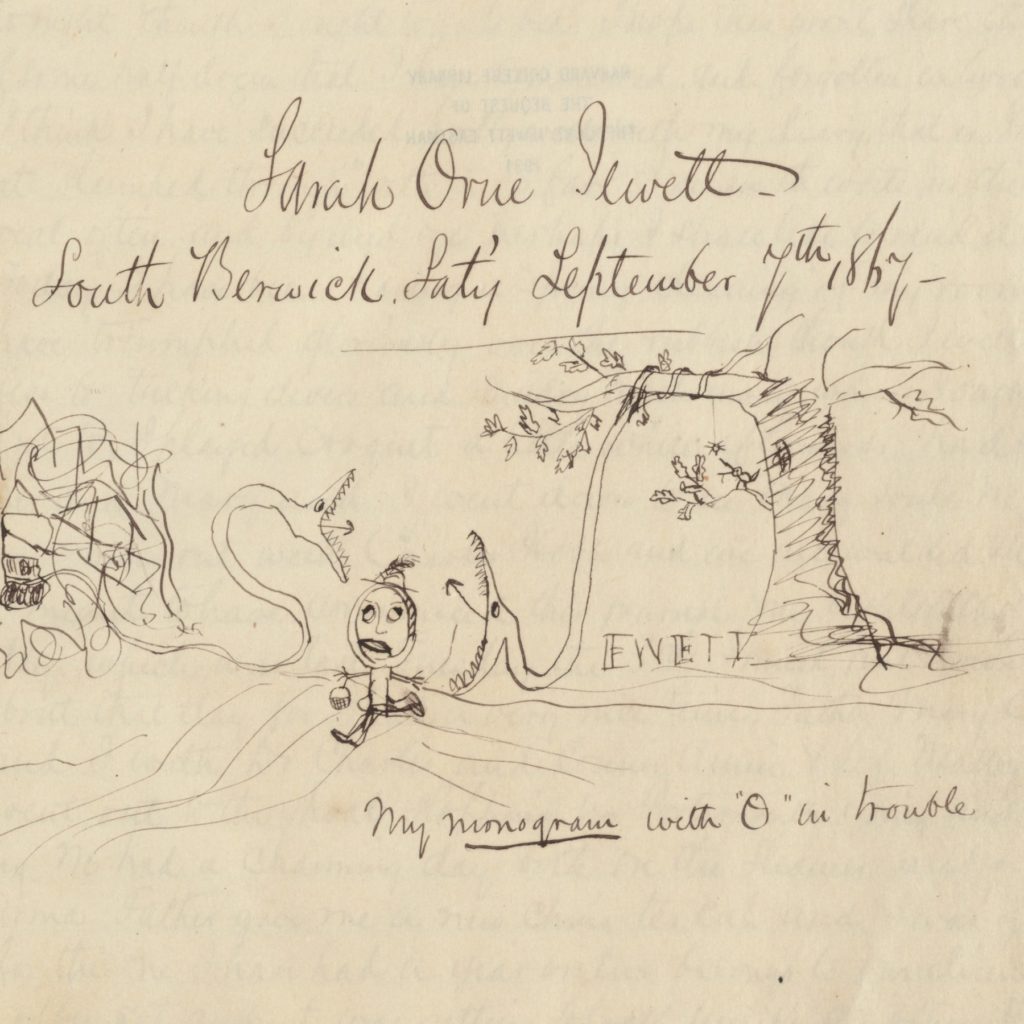

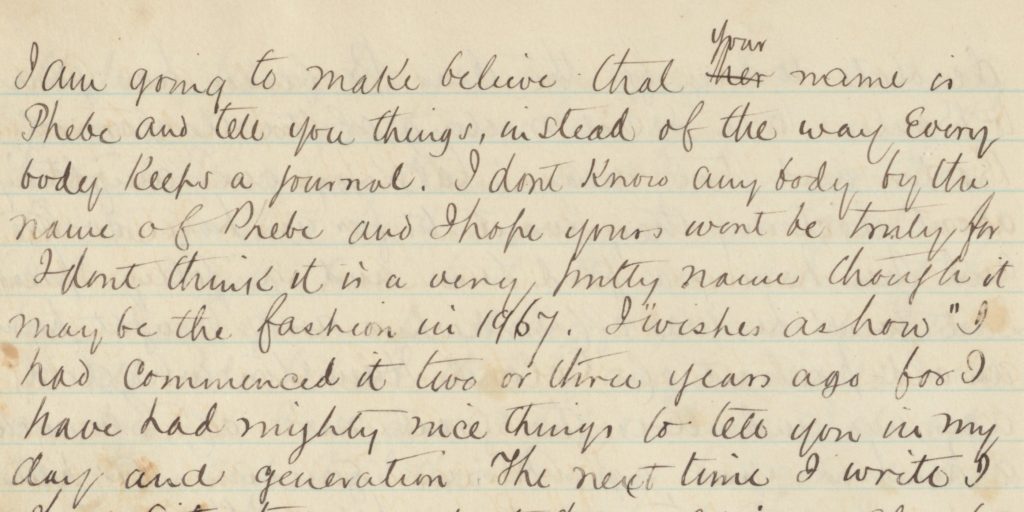

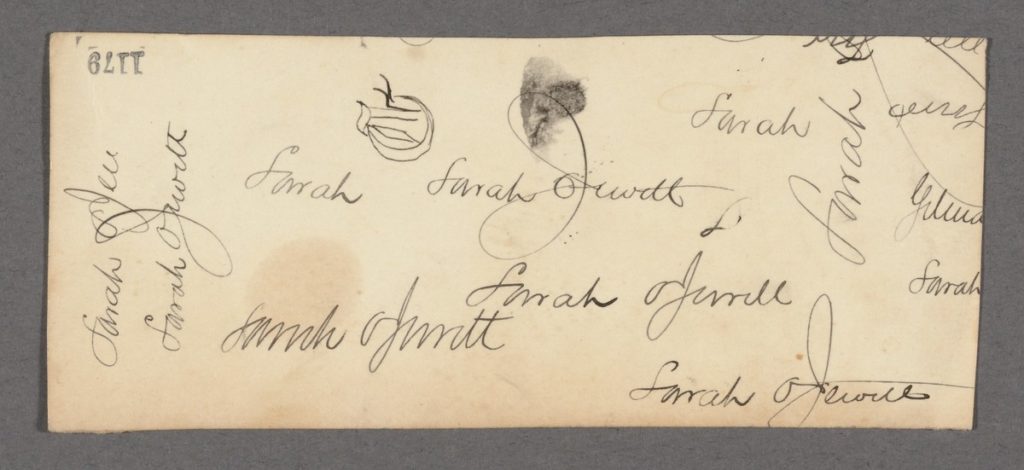

At a young age, Sarah Orne Jewett imagined herself living a life less ordinary. From her diary entries, to her penchant for doodling her signature, one senses a strong identity present.

Confessions of a House-Breaker

“This confession differs from that of most criminals who are classed under the same head; for whereas house-breakers usually break into houses, I broke out.”

–Sarah Orne Jewett (“Confessions of a House-Breaker,” 1883)

This opening to a dream-like morning encounter with nature seems to mirror Jewett’s own journey.

In diary entries from her teenage years, Sarah expressed an aversion to marriage. This feeling seems to have been both curious to her, as on her feelings about cousin Helen Gilman’s marriage, “I hate to have her married, though I can give no definite reason,” (September 21, 1867)* and known in some deep part of herself: a week later, after the wedding, she wrote, “after Helen Williams Gilman was no more, they went up and congratulated her.” (September 29, 1867)*

At the same time, Jewett experienced romantic feelings towards girlfriends, from momentary rushes over sharing a bed to intense infatuations with exchanges of rings, to falling in love.

Intimate female friendships that bordered on amorousness were not unusual in the nineteenth century. Young women were encouraged in these so-called “romantic friendships,” to ready them for marriage in a culture that otherwise ill-prepared them.

Yet, Jewett makes no mention of attraction to men or to envisioning becoming herself a bride. Instead, there is a defiant childlike quality in her writing, as if she perhaps seeks an escape from what looms ahead.

It was not uncommon for a woman to remain single in the Victorian era—Sarah’s sister Mary did not wed. For women of the time, marriage was directly connected to economic well-being. If one did not need to marry to avoid becoming a financial burden on their family, many times the safer choice was to not to; marriage in the nineteenth century (and before) was a gamble. A married woman quite literally lost her legal identity. In this, she lost the ability to regain her freedom if the union was a disaster.

For Jewett, the drive for independence seems to have gone beyond spinsterhood; she was determined to have a writing career, persevering through several rejections before being published. She suffered through two depressions in her early twenties. When she gained momentum as a writer, publishing her first novel, Deephaven, at the age of twenty-eight, the depression seems to have lifted.

Success as a writer meant freedom.

As a writer, Jewett over and over again created strong female protagonists who broke out of barriers, literally and figuratively.

When Sarah Orne Jewett and Annie Fields fell in love, they formed a relationship that was mutually nurturing and caring, and one in which Sarah Orne Jewett—S.O.J.—could keep her identity.

* MS Am 1743.26, Item 3, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Queer Perspective

Among Jewett’s greatest strengths as a writer are the depictions of her female characters and the bonds of friendship between women. Sarah Orne Jewett fell in love with several women in her life, finally finding the relationship she sought with Annie Fields. In a few works, Jewett seems to be portraying lesbian love. Another work has been put forth in academia as the first gay American novel.