Sarah Orne Jewett House

Sarah Orne Jewett House

Mary's Room

Mary Rice Jewett had the room that would today be called the master bedroom, once belonging to her grandfather, Captain Theodore Jewett and before him original homeowner John Haggens. For these gentlemen of an earlier era, the chamber was used not only as private space, but a public one as well, a place to do business and entertain. The room’s architectural details, with carved cornices and paneling, and its extraordinary luminescent wallpaper, would have been impressive to friends and business associates of the two entrepreneurs.

Mary Rice Jewett had the room that would today be called the master bedroom, once belonging to her grandfather, Captain Theodore Jewett and before him original homeowner John Haggens. For these gentlemen of an earlier era, the chamber was used not only as private space, but a public one as well, a place to do business and entertain. The room’s architectural details, with carved cornices and paneling, and its extraordinary luminescent wallpaper, would have been impressive to friends and business associates of the two entrepreneurs.

As Jewett chatelaine and central figure of the town, Mary Rice Jewett seems the fitting occupant for the grand room.

Details of Mary's Room

Mary’s Room Wallpaper

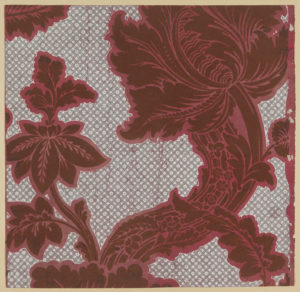

This flocked wallpaper with mica was made in England between 1770-80.

Flocked wallpapers were made by applying a gluey substance in a decorative pattern to the paper and running it through a trough filled with finely chopped particles of silk or wool to create a velvety pile. Mica could also be applied for sparkle. No doubt installed around the time the house was built in 1774, it’s one of only five eighteenth-century flocked papers to survive in situ on walls in New England.

Before and during the Revolution, imported English wallpapers were highly prized symbols of status. An even earlier example in Historic New England’s collections was in the Hancock House in Boston and may date from as early as 1737 when the house was built.

Portrait of Mary

Mary Rice Jewett, Helen Bigelow Merriman (1844-1933), pastel, c. 1900

In a speech read before the Worcester Art Society in 1891, the painter of Mary Jewett’s portrait, Helen Bigelow Merriman, explained how the best portraits are created.

It is most essential . . . [that] a pose should be decided on that is at once noble and characteristic, that an attitude should be found in which the sitter feels natural, and yet one which has some dignity and outlook.

Here, Mary is captured with a slight smile that suggests her essential character was that of a contented and centered woman. The artist was a close friend of the Jewetts and would have understood exactly the type of woman Mary was.

We know how important Mary was in Sarah’s life. This portrait hung over the desk in their nephew’s office, suggesting how important she was to him as well.

We know how important Mary was in Sarah’s life. This portrait hung over the desk in their nephew’s office, suggesting how important she was to him as well.

Photographs of Sarah and Annie

Sarah and Annie’s photographs are displayed on the west wall of Mary’s room, as they were in the 1931 photograph of the space.

Mary Rice Jewett and Annie Fields were friends; they occasionally corresponded and often send each other regards through Sarah. Gifts were sent, particularly flowers from the Jewett garden.

As Sarah’s health failed at the end of her life, Annie wrote, “It is good to have Mary’s words when you are not quite up to a vast correspondence. Will you tell her so with my love and thanks.” Annie Fields, (Letter to Sarah Orne Jewett, undated) MS Am 1743.1 (33), Houghton Library, Harvard University

If there was any tension between Annie Fields and Mary Rice Jewett, it was minor, and not over Sarah’s relationship, but over her presence. Annie rarely came to South Berwick; it is likely that the Maine town did not suit her. Annie invited Mary to Boston, but often declined invitations to South Berwick. Likewise, Mary enjoyed having Sarah with the family at home, though she did spend time with her sister and partner in Boston and at their summer home in Manchester. In the end, Sarah Orne Jewett traveled between the two houses, spending time at each.