Sarah Orne Jewett House

Sarah Orne Jewett House

The Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries

Mariners and Traders As Maine communities evolved in the seventeenth century, Maine itself became a part of Massachusetts in 1677; Maine did not achieve statehood until 1820. The area that eventually became the town of South Berwick, retained its Wabanaki name, Quamphegan, until 1814, when South Berwick incorporated as a village.

As Maine communities evolved in the seventeenth century, Maine itself became a part of Massachusetts in 1677; Maine did not achieve statehood until 1820. The area that eventually became the town of South Berwick, retained its Wabanaki name, Quamphegan, until 1814, when South Berwick incorporated as a village.

Colonists in seventeenth and eighteenth-century Southern Maine were looking to build an economy and wood was an available commodity. They sold timber for export. Trade that involved processed timber—shipbuilding and ship parts, such as masts, and wooden barrels—all became major aspects of trade.

The Maine shipbuilding trade flourished. The wood from Maine trees was an inexpensive raw material, and that translated to profit. Sea captains sailed to ports around the world with cargoes of timber and other exports, such as fish and fur. The fur trade died out as beavers were nearly eradicated. Fish continued to be an export; fish considered of lesser quality were sent to the West Indies to supply meager food for enslaved people on sugar plantations there.

Slavery in Southern Maine

To grow a strong economy, Maine settlers needed labor.

In 1650, England’s Oliver Cromwell won a battle aimed at unifying Scotland with the crown. As a result, some of the captured Scottish soldiers were involuntarily shipped to the American colonies and enslaved. Twenty-five of these enslaved were sent to Quamphegan and indentured—they could earn back their freedom through labor.

The name Berwick originates with the Scottish indentured. Eventually assimilated as free citizens, they began using Scottish names for area places. They called the area “Barwicke,” which became Berwick.

At the same time, a series of worsening conflicts threatened the stability of settlements. From 1675-1783, a series of deadly conflicts waged between the Indigenous allied with the French, and the British.

Misunderstanding Wabanaki cultural diplomacy, the settlers exploited them as a source of labor. If tribes refused to comply, they faced eradication. As the situation became dire, the Wabanaki fought to defend their land and rights. During these conflicts, sometimes intentionally provoked for labor potential, settlers captured and enslaved hostile groups.

By the second decade of the eighteenth century, the Wabanaki were all but eliminated from the region.

Enslavement of the indigenous paved the way for the importation of enslaved of Africans to Maine.

According to Patricia Q. Wall in her work, Lives of Consequence (Portsmouth Historical Society, 2017), by 1781, there were between fifty and one hundred enslaved African people living in the area surrounding Berwick. In 1783, Massachusetts effectively abolished slavery through a court ruling, however, the practice of enslavement continued in many places for years following the ruling.

Thus, much of Southern Maine’s foundations of prosperity were built on the backs of people in bondage.

Many enslaved people actively engaged in resistance, through escape, the most common, work stoppage, and even sabotage. Many found ways to obtain manumission by purchasing their freedom through earning income or, in the case of Prince of York, Maine, by joining the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War.

Enterprising William Black, or Black Will, saved enough money while enslaved to purchase a tract of land in nearby Eliot, Maine, establishing a farmstead there upon gaining manumission.

Free blacks settling in Maine during this time worked in any number of occupations, most coming to the area in the maritime trade—sailing, fishing, and working on ships.

Caesar

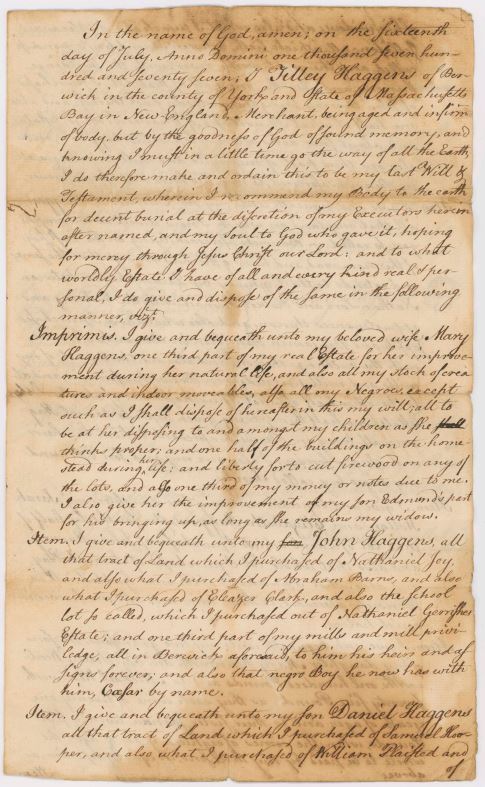

John Haggens was a son of Tilly Haggens (d. 1777) an Irish immigrant who settled in Berwick with his family, became a shopkeeper and bought up a good deal of land in the middle of what is now South Berwick.

John Haggens was a son of Tilly Haggens (d. 1777) an Irish immigrant who settled in Berwick with his family, became a shopkeeper and bought up a good deal of land in the middle of what is now South Berwick.

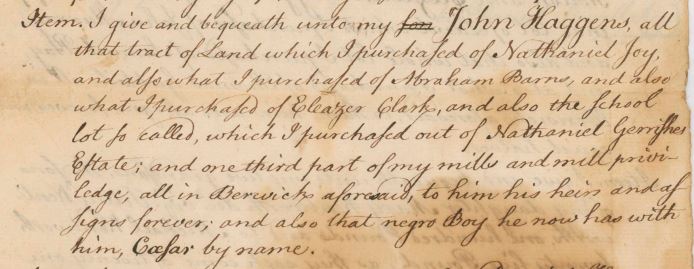

In his last testament and will, Tilly Haggens bequeathed four tracts of land and a third of his mills to John. In the same will and testament, Tilly Haggens bequeathed to his son John an enslaved person, Caesar.

As yet, nothing is known of Caesar. This is because few records were kept of enslaved people, and because enslaved people were robbed of their most personal possessions—their names, first names and surnames. There was a lot of crossover in names assigned to enslaved people, with names derived from myth, biblical references, and given as jokes—Caesar, Cato, Dinah, and Prince were all common names given to the enslaved.

John Haggens

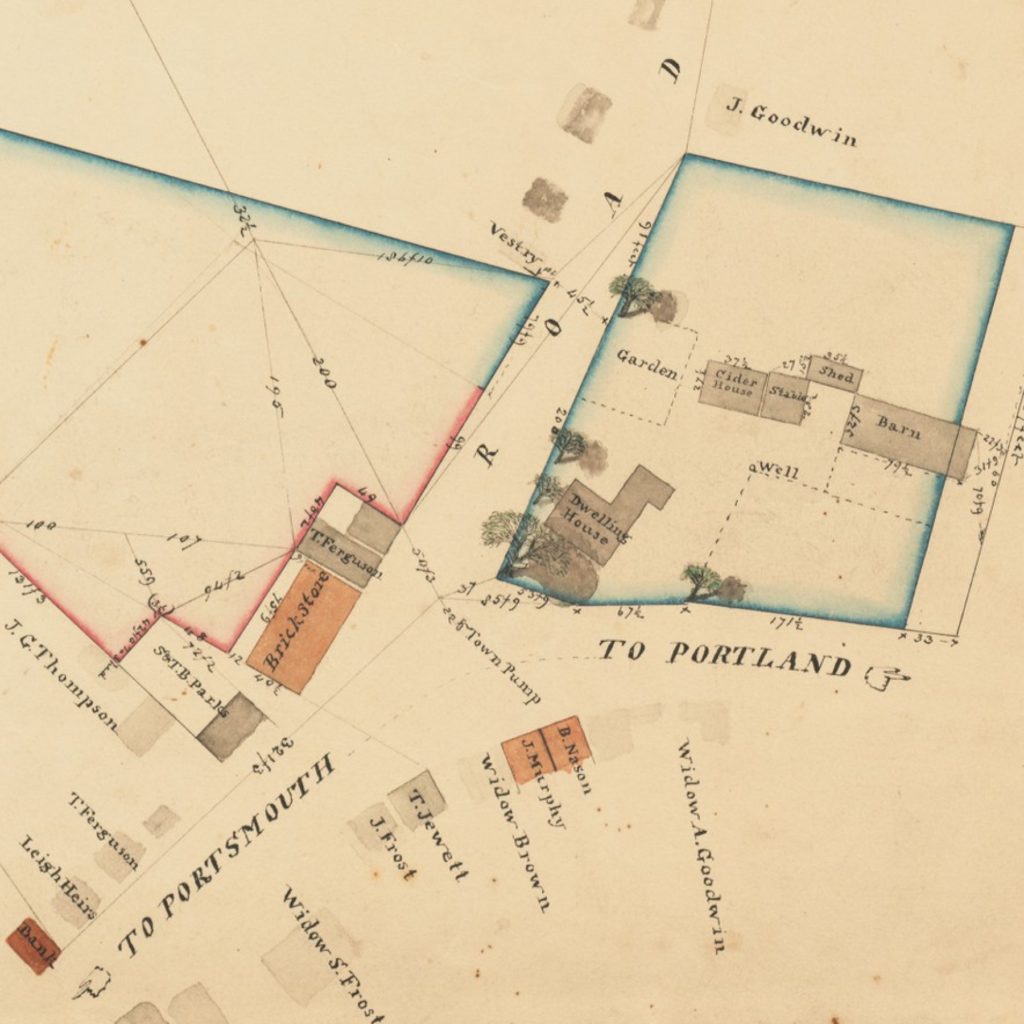

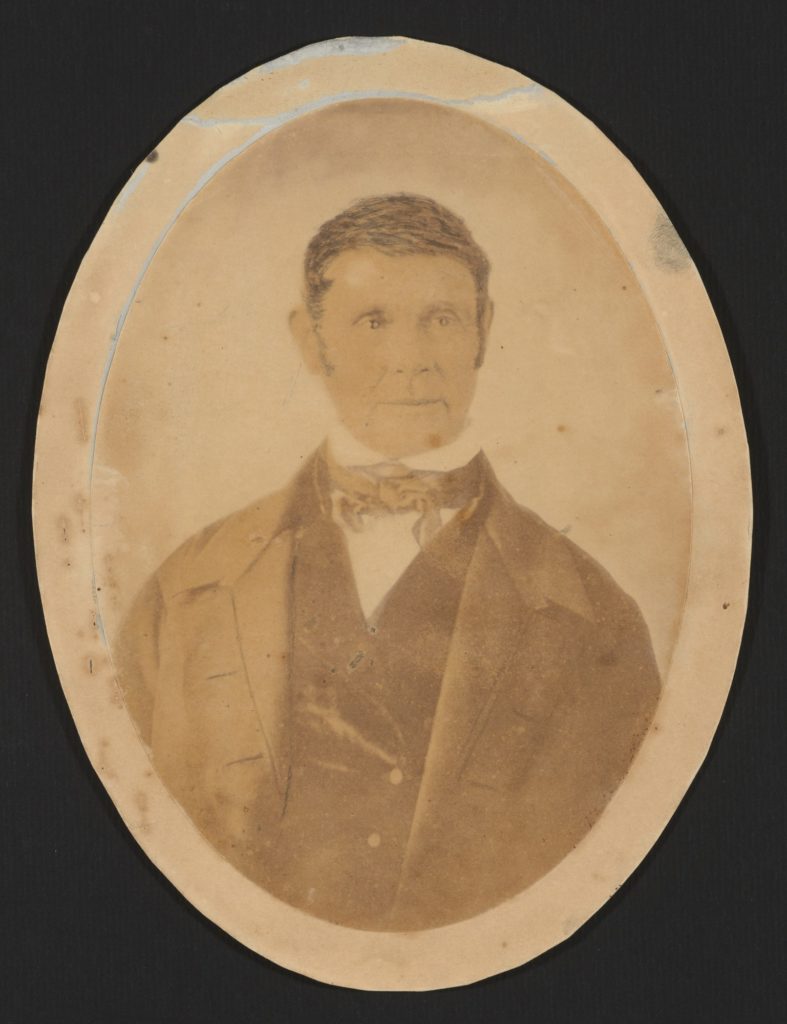

John Haggens (1742-1822) was an entrepreneur-trader like his father. According to Old Berwick Historical Society, the tax census of 1798 lists him as one of the two wealthiest men in town.

Between 1774 and 1780, Haggens built the house that would eventually belong to the Jewett family, and in which Sarah Orne Jewett was born. Wallpaper on the second floor of the house goes back to his ownership; this is documented by the king’s stamp on a section of the paper, proof that the paper was imported prior to American Independence.

Between 1774 and 1780, Haggens built the house that would eventually belong to the Jewett family, and in which Sarah Orne Jewett was born. Wallpaper on the second floor of the house goes back to his ownership; this is documented by the king’s stamp on a section of the paper, proof that the paper was imported prior to American Independence.

In 1901, Sarah Orne Jewett wrote the novel, A Tory Lover, set in South Berwick, on the eve of the American Revolutionary War. This historical fiction romance novel brings together fictional characters with actual people from the past. Tilly Haggens is a character in the book. Also a character in the book: Caesar, a Guinea prince who has been enslaved and works for Haggens.

Captain Theodore F. Jewett

From her grandfather, Captain Theodore F. Jewett, Sarah would have heard stories of life at sea. Theodore F. Jewett ran away to sea when he was just a boy. As an adult, he became a sea captain, sailing ships laden with timber and other exports, likely fish, to the West Indies, where the crew unloaded cargo and loaded on rum and molasses—items directly involved with the trafficking of enslaved people. Assisted by his brother Thomas, Captain Jewett was involved in shipbuilding and opened a mercantile in town, selling West Indies goods such as molasses, sugar, coffee, and cocoa.

Captain Jewett and his brother Thomas Jewett became the wealthiest men in South Berwick. In 1819, Captain Jewett rented the house on the corner lot in South Berwick—the largest and grandest house in the middle of town—and by 1831, he owned the house.

In the house, a Georgian manse built some fifty years prior, Captain Jewett had a desk—the same desk at which Sarah Orne Jewett would later write—on the second-floor hallway. From there, he could look out onto the town and to his mercantile store.

In the house, a Georgian manse built some fifty years prior, Captain Jewett had a desk—the same desk at which Sarah Orne Jewett would later write—on the second-floor hallway. From there, he could look out onto the town and to his mercantile store.

Captain Jewett married four times. Wife Sarah Orne Jewett, for whom the author was named, died at twenty-five. His second wife Olive Walker, the daughter of a sea captain, died at thirty-two. His third wife, Mary Rice Jewett, of whom Sarah’s sister is the namesake lived until 1854. She was the first of the grandfather’s wives whom Sarah knew, and to Sarah, she was quite intimidating. Captain Jewett married a fourth time, to Eliza Sleeper Jewett, his brother Nathan’s widow. Eliza survived Captain Jewett, living to Sarah’s young adulthood. With grandmother Eliza, Sarah found a friend and a font of stories.