Sarah Orne Jewett House

Sarah Orne Jewett House

A Place to Write

Sarah Orne Jewett wrote in “Lady Ferry,” Old Friends and New, “One often hears of the influence of climate upon character; there is a strong influence of place, and the inanimate things which surround us indoors and make us follow out in our lives their own silent characteristics. We unconsciously catch the tone of every house in which we live, and of every view of the outward, material world which grows familiar to us, and we are influenced by surroundings nearer and closer still than the climate of the country which we inhabit.”

Jewett was born in her grandfather’s house and grew up next door in a house built on the family compound. As a child, she sat on the fence lining the property and watched townspeople coming and going in the village center. Often spending time in the house of her grandfather, a retired sea captain, she would have heard the stories of old sailors and traders, those of the cooks and maids bustling around the house, and those of her step-grandmother, with whom she was close. A “wild and shy” child, she preferred the woods, fields, and river to the indoors, and books to the classroom.

As an adult, Jewett wrote at her grandfather’s desk in the second-floor hall, by a large front window overlooking the town center and the people of South Berwick. The choice of writing place seems apt for an author who followed her father’s advice: “Show people as they are.”

As an adult, Jewett wrote at her grandfather’s desk in the second-floor hall, by a large front window overlooking the town center and the people of South Berwick. The choice of writing place seems apt for an author who followed her father’s advice: “Show people as they are.”

Editor and friend William Dean Howells wrote, in a 1903 letter to Sarah Orne Jewett, “Your house will always remain a surprise to me, not because it was not the fittest possible setting for such literature as yours, but just because it was.”

Sarah's Desk

A Place to Write

“Miss Jewett’s ‘den’ is the most delightful I have ever seen. It is in the upper hall, with a wide window looking down on the tree-shaded village street. A desk strewn with papers is on one side and on the other a case of books and a table. Pictures, flowers and books are everywhere.”

Sarah Orne Jewett (interview, Philadelphia Press, 1895) Colby College Special Collections, Waterville, Maine

Click on the spots to discover some of Jewett’s personal and published writings, as well as an inspirational quote from the nineteenth century French novelist Gustave Flaubert that she kept close by.

[no date]

My dear Miss Putnam,

This is the first pen, and it is all you said it was! I have learned long ago that some pens have a motive power of their own, and some have to be driven wearily along the page -- But oh! what a dear and charming box you put them in with an S.O.J. that can never sleave any doubt of the proud and happy owner. I love to have associations with the things I keep on my desk -- all my little tools! and this will often and often remind me of you with such a happy thought of your remembrance….

Yours sincerely

Sarah O. Jewett

Sarah Orne Jewett (Letter to Georgina Lowell Putnam, niece of James Russell Lowell, on receipt of a gift pen). Mss SL 262 (1-4), Spence and Lowell Family Papers, The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA

From “The Flight of Betsey Lane”

“Miss Peggy Bond was a very small, belligerent-looking person, who wore a huge pair of steel-bowed spectacles, holding her sharp chin well up in air, as if to supplement an inadequate nose. She was more than half blind, but the spectacles seemed to face upward instead of square ahead, as if their wearer were always on the sharp lookout for birds.

Sarah Orne Jewett (“The Flight of Betsey Lane, collected in A Native of Winby, 1893)

“…but the discovery was soon made that Mrs. Todd was an ardent lover of herbs, both wild and tame, and the sea-breezes blew into the low end-window of the house laden with not only sweet-brier and sweet-mary, but balm and sage and borage and mint, wormwood and southernwood. If Mrs. Todd had occasion to step into the far corner of her herb plot, she trod heavily upon thyme, and made its fragrant presence known with all the rest. Being a very large person, her full skirts brushed and bent almost every slender stalk that her feet missed. You could always tell when she was stepping about there, even when you were half awake in the morning, and learned to know, in the course of a few weeks' experience, in exactly which corner of the garden she might be.”

- Sarah Orne Jewett (II. “Mrs. Todd,” The Country of the Pointed Firs)

Dear love I am so often sending you messages -- and I hope the 'little white mother' don't forget them by the way -- Are you sure you know how much I love you? If you don’t, I can't tell you! but I think of you and think of you and I am always being reminded of you.

I am yours most lovingly -- S. O. J

- Sarah Orne Jewett (Letter to Annie Fields, March 1882), MS Am 1743 (255), Houghton Library, Harvard University

"Écrire la vie ordinaire comme on écrit l'histoire.”

--Gustav Flaubert (In English, “Write ordinary life as we write history.” Sarah Orne Jewett kept the quotation on her writing desk)

Letter to Annie, “The Dulham Ladies” (talks about writing)

Tuesday evening

24 November 1885

Dear Fuff

I am so glad to have you home again. Yes, you did leave your little book here and I did not suppose you would want it until I came, so it was not sent. I daresay I should have forgotten it, too, but I will not now. What a dismal day! but it is almost the first very bad one. It has snowed a little here and been chilly and dark, and I have felt a little stiff and found it hard to shake off my cold, though it is a good deal better.)

I have been busy putting “The Dulham Ladies” in order, but I really am afraid it is not the thing for the Atlantic. There are funny places in it, and yet with all the good bits it does not make a good whole thing -- I will bring it up and let the Linnet see it, because I promised, but it will do better for the Independent and I shall say so frankly -- I can give him “The Gray Man. ”

-- All these last stories lack something. I want to say "Well what of it?" when I finish reading them -- I am ashamed to say that I think I shall get on better another year for why didn't I get on well this year except that last winter's siege took the goodness out of it --

…I wish I could sleep through Thanksgiving Day! but I am going to try to be good -- Good night from tired and bad Pinny but one that loves you.)

Sarah Orne Jewett (Letter to Annie Fields, November 24, 1885) MS Am 1743 (255), Houghton Library, Harvard University. MS Am 1743 (255). Transcription by Terry Heller, Coe College.

The little English sparrows flit in the lilac bush outside;

I like to watch the busy things. There's one that's tried and tried

To break a string the children tied around a branch one day;

How hard he pulls it with his beak! Now he has flown away.

- Sarah Orne Jewett (“Waiting,” Our Continent, April 26, 1882)

to learn more

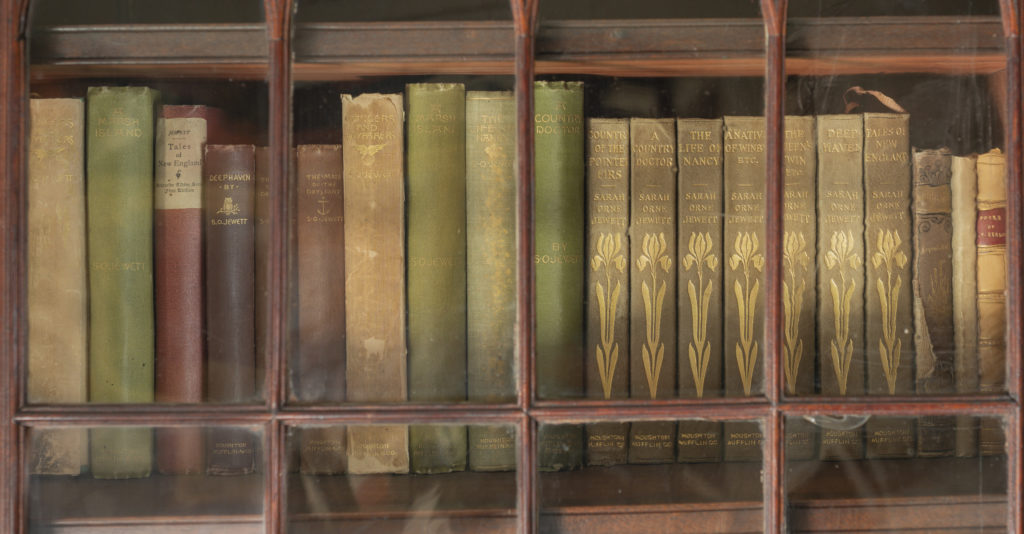

Books in Sarah's Secretary

Feminist Undertones

For the better part of the twentieth century, Sarah Orne Jewett was recognized almost exclusively as a regionalist writer. Recent examinations of her work have asserted that Jewett was much more. For Jewett, a driven pursuit of career and freedom informed her work. So too did the value she placed on female friendships and a community of women. Feminist themes evolved in her work, from the subtle to the straightforward and beyond, to a work both refined and grounded. This photograph was taken on the occasion of Jewett receiving an Honorary Doctorate of Letters from Bowdoin College, an all-male institution, in 1901.

Inspiration: Deephaven

Sarah Orne Jewett’s first novel, Deephaven (1877), centers on the escapades of two friends, Kate Lancaster and Helen Denis, who summer together at a house Kate’s mother has inherited, in the town of Deephaven, Maine.

The character of Kate Lancaster is believed to be inspired by Jewett’s friend Kate DiCosta Birckhead, for whom Jewett appears to have had romantic longings.

Jewett was inspired to use the house of her birth as the model for the fictional manse, noting in the book details from the front hallway, dining room, library, and second floor rooms, including a pointed description of the wallpaper in the parlor chamber, later Mary’s room.

The novel was a success; a second edition was printed in 1894 with illustrations by Marcia Oakes Woodbury and Charles Woodbury. To have the illustrations created, Jewett invited the artist couple into her home to sketch. Pictured here is one of the Woodbury illustrations for the book. The drawing hangs in the dining room.