Sarah Orne Jewett House

Sarah Orne Jewett House

The Writer

Sarah Orne Jewett is best known for two of her major works, The Country of the Pointed Firs (1896) and “A White Heron,” (1886).

In her day, Jewett was an internationally celebrated writer. She wrote over three hundred works, including fiction, essays, and poetry.

By the late twentieth century, Jewett’s fame had declined.

Much of the reason for her diminished light is the literary criticism—white-male centered—that dominated the mid-twentieth century.

Dismissed as quaint and regional, Jewett’s contribution to literature was overlooked.

Recently, scholars have rediscovered her work and there is renewed interest in the deft depictions of women, the subtleties of relationships, and the feminist undertones in her work.

Influences and Mentors

A small gallery of portraits hangs in the library of Sarah Orne Jewett’s house; this same gallery appears in the 1931 photographs taken of the house when Historic New England acquired the site. It is likely that the portraits have hung on this wall since Jewett’s time, as sister Mary and nephew Teddy preserved aspects of their famous sister in the house.

The gallery includes portraits of four preeminent poets and writers of the nineteenth century; their influence on Jewett’s writing can be seen in different aspects of her work. Also included here are portraits of two influential writers gracing other walls in the house.

Another writer, Harriet Beecher Stowe, while not represented in the house, was described by Jewett herself as an influence, and so is included here.

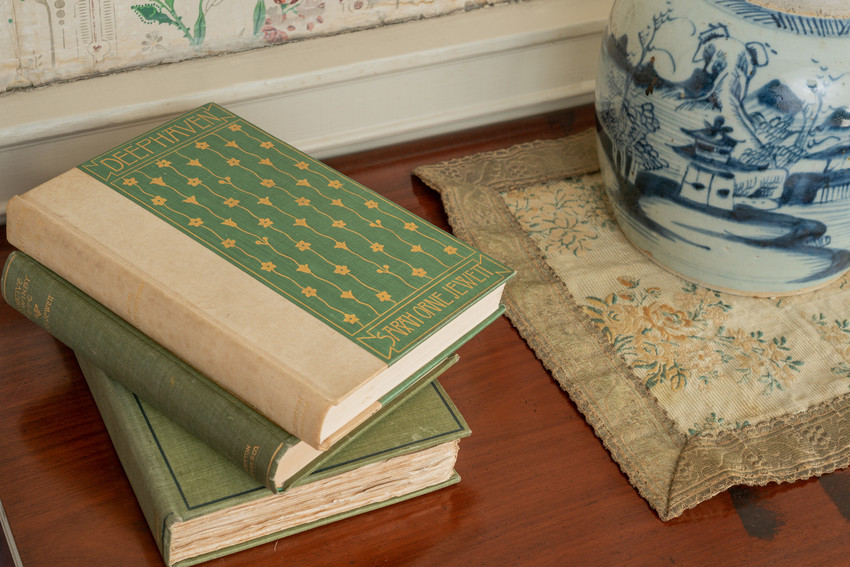

Book Covers

Designs of a Friend

Sarah Orne Jewett’s dear friend Sarah Wyman Whitman designed her book covers with a simple and elegant look in the Arts and Crafts style.

Whitman began studying painting with noted artist William Morrison Hunt, and with Hunt’s teacher Thomas Couture in Paris. She became interested in the Arts and Crafts movement and began working in stained glass and in book cover design.

At its core, the Arts and Crafts movement was a reaction against industrialization. The movement rejected mass production, finding it dehumanizing, and instead prized handcrafting and the individual artist. The movement placed attention on beauty in functional, everyday objects and so focused more on the decorative arts such as ceramics, handmade textiles, furniture, jewelry, and books than on painting and sculpture. Sarah Wyman Whitman was a founding member of the Boston Arts and Crafts Society (1897).

1868 "Jennie Garrow's Lovers"

Jewett published her first story in “Flag of Our Union” under the name A. C. Eliot, but did not mention it later in her career, usually referring to her first story as “Mr. Bruce,” published a year later. Still, while Jewett has not quite found her voice in this fledgling piece, it is interesting as the beginning of Jewett’s evolution as a writer. For example, Jewett employs the narrator storyteller, a convention she returned to often, later more skillfully.

Sarah as Mentor

Willa Cather

When a carriage accident effectively ended Jewett’s ability to write productively (she suffered ongoing and severe headaches and neck pain), she continued to write letters to friends and family, and now, mentored the emerging and admiring writer Willa Cather.

She gave Cather advice that Cather later credited with her growth as a writer, including from a 1908 letter: “…You must find your own quiet centre of life, and write from that to the world that holds offices, and all society, all Bohemia; the city, the country – in short, you must write to the human heart, the great consciousness that all humanity goes to make up. Otherwise what might be strength in a writer is only crudeness, and what might be insight is only observation; sentiment falls to sentimentality – you can write about life, but never write life itself.” (13th of December, 1908), Annie Fields, Letters of Sarah Orne Jewett (1911).

Later, in her preface to the 1925 collection The Best Stories of Sarah Orne Jewett, Cather wrote that The Country of the Pointed Firs was one of three books by American authors (with The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, by Mark Twain, and The Scarlet Letter, by Nathaniel Hawthorne), “which have the possibility of a long, long life.”

Willa Cather photo credit: Photo Credit: Pho-4-RG1951-1750. WCPM Collection. Willa Cather Foundation Special Collections and Archives of the National Willa Cather Center, Red Cloud Nebraska